The Iberian Lynx

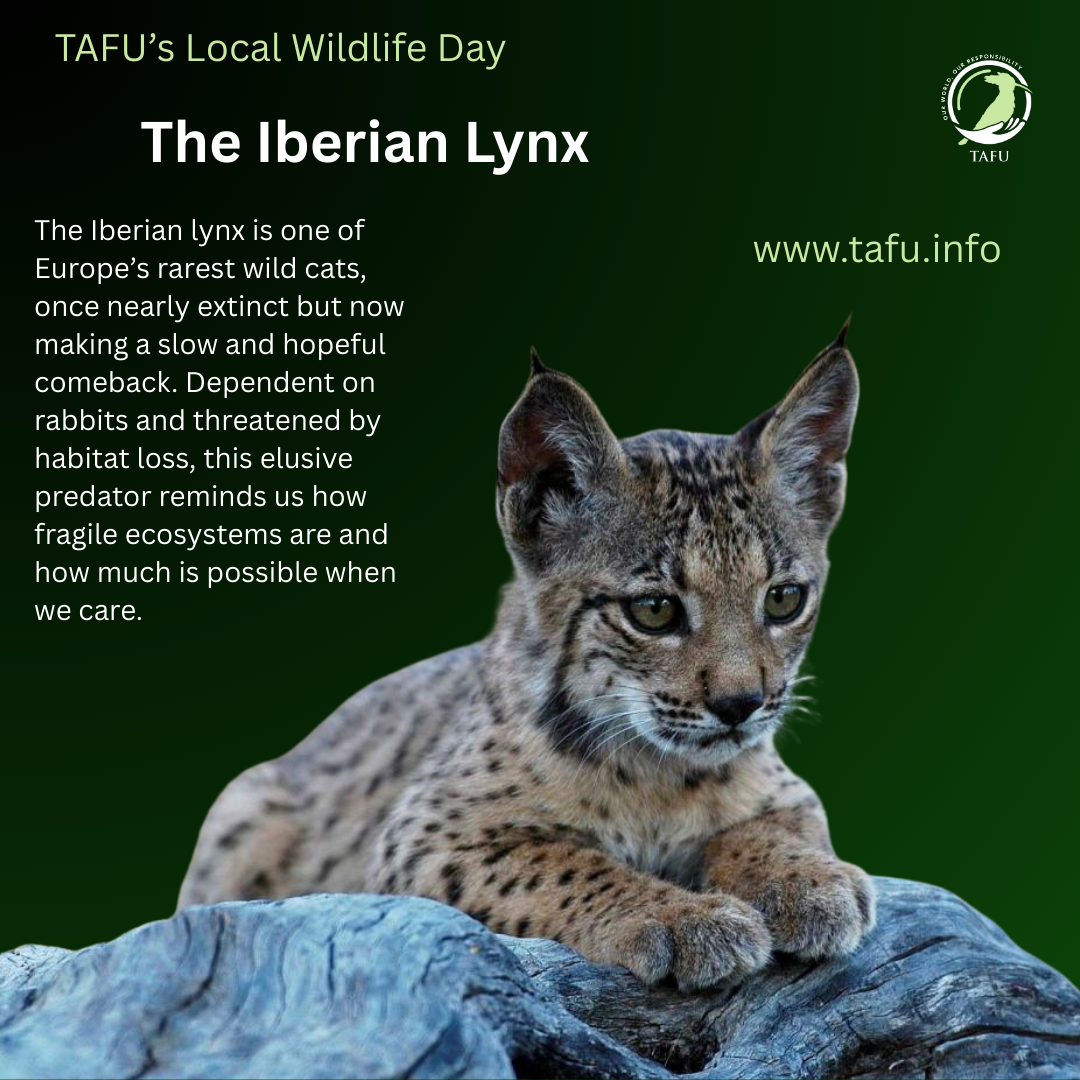

Since I’m in Spain I thought I ought to write about a local Spanish species; the Iberian lynx (Lynx pardinus). It is one of Europe’s most endangered mammals, a solitary and elusive predator of the cat family that once roamed freely across the Iberian Peninsula. With its striking spotted coat and characteristic ear tufts, the Iberian lynx has become both a symbol of wild beauty and a living lesson in the consequences of human intervention.

Recognisable by its compact, muscular build and graceful gait, the Iberian lynx typically measures 75 to 100 centimetres in length, with a short tail ending in a dark tip. Standing 45 to 70 centimetres at the shoulder and weighing 13 to 15 kilograms, this species is smaller and more finely built than its northern cousins.

Its coat ranges from yellowish to reddish-brown, patterned with black or dark brown spots that vary from dense clusters to sparser markings. Researchers identify three main coat patterns across individuals. A pale underbelly and a pronounced facial ruff add to its distinguished lynx appearance. The black tufts at the tip of the ears are not merely decorative; they enhance the lynx’s sense of hearing, vital for hunting in dense Mediterranean vegetation.

The Iberian lynx lives mostly in the scrublands and oak forests of southwestern Spain, particularly within protected national parks. Though it once thrived across Portugal and Spain, its range has now dramatically shrunk due to human expansion.

Its diet consists almost entirely of wild rabbits (Oryctolagus cuniculus), which it stalks and ambushes with precision. This dependency on a single prey species means that fluctuations in rabbit populations have a direct and dangerous impact on the lynx’s survival. On rare occasions, it may hunt birds or small deer, but its entire evolution has shaped it to hunt rabbits in thick, low cover.

The decline of the Iberian lynx is a lesson in how quickly a species can be pushed to the brink. Its population plummeted not because of one catastrophe but due to a combination of pressures. As traditional bushland was cleared for agriculture, eucalyptus plantations, and urban developments, the lynx lost its territory. Roads and railways cut across its hunting grounds. Dams submerged entire habitats.

When rabbit populations collapsed due to disease, the lynx lost its food source. Unable to adapt quickly to new prey or new environments, its numbers dwindled alarmingly. By the early 2000s, fewer than 100 individuals remained.

The Iberian lynx is now listed in Appendix I of CITES and on the IUCN Red List as Endangered.

In response, governments, scientists, and conservation organisations worked together to reverse the decline. Captive breeding programmes, habitat restoration, and anti-poaching initiatives have helped stabilise numbers. Rewilding projects and protected corridors have allowed some lynx to be reintroduced to their native habitats.

By 2020, the Iberian lynx population had climbed above 400. Still fragile, still fragmented, but there. The success of these efforts offers hope not only for the lynx, but for other species on the brink.

The Iberian lynx teaches us more than facts about ecology. It teaches us about balance between growth and preservation, between economy and ecology. When we fragment habitats, we fragment lives. When we favour monocultures over biodiversity, we endanger more than just rabbits, we endanger the whole food chain, and whole habitats.

The Iberian Lynx is a reminder that every species plays a role in its ecosystem. Remove one, and the balance shifts. Protect and the ecosystem begins to recover.

Nature does not ask for much, just space, silence, and time to live and recover. The Iberian lynx is still here, watching from the shadows of the Mediterranean woods. So, if we remember to give nature the space and just start reversing the damage we do, it will bounce back!